Freshers’ week lasts forever…right?

I’ve made it halfway through my final year as a BA English and History student, and there’ve been many painful moments of realisation over the last few months. Despite my best attempts to keep the work-play mix in checks and balances, as I slump to the library for another daily grind I find myself lamenting the slow and painful death of my social life. Perhaps the saving grace stopping me from going completely mad is the fact that my course-mates seem to be going through the same thing. So here are ten symptoms well known to those battling through the final year of their arts degree:

You know exactly what you want to do after you graduate…just kidding

You’re really glad you chose an arts degree, because they have the best possible reputation for post-graduate employment, and you don’t know which job offer to accept next September. See you in Costa Coffee, future baristas.

Your social life has become that of an ageing bohemian

I never thought I’d go to a cheese and wine night until I was in my 30s, but arts students hold them regularly as a happy medium between a night on the town and a night on the sofa. Good food, great alcohol, even better company and none of the annoyances of jostling about in a sweaty nightclub with a bunch of strangers. It’s pretty em-mental. Sorry.

Someone just recalled the one library book you need over the Christmas holidays, and it caused you to have had an existential meltdown

But that’s the one book…what do they need it for…I can’t write my essay now…may as well not do it…why did I choose this degree…life is pointless.

You’ve finally given in to using a backpack daily

Remember that canvas tote bag that you used to use all the time? No, you probably don’t, because you ditched it in September when it became heavy enough to use as a hammer throw. Now you’ve succumbed to using your Roxy rucksack to carry your books to the library. Mum always did say something about comfort over style…

You’ve been studying so hard you forget which words are real- and invent your own

Last week, at the end of an eight hour library stint, I used the word ‘premacy’ in my essay, to discover that it is not a word, other than being the name for a Mazda minivan. Primacy is a word, as is pre-eminence, but premacy is definitely not a real word.

The Mazda Premacy is delightful but not what I need right now

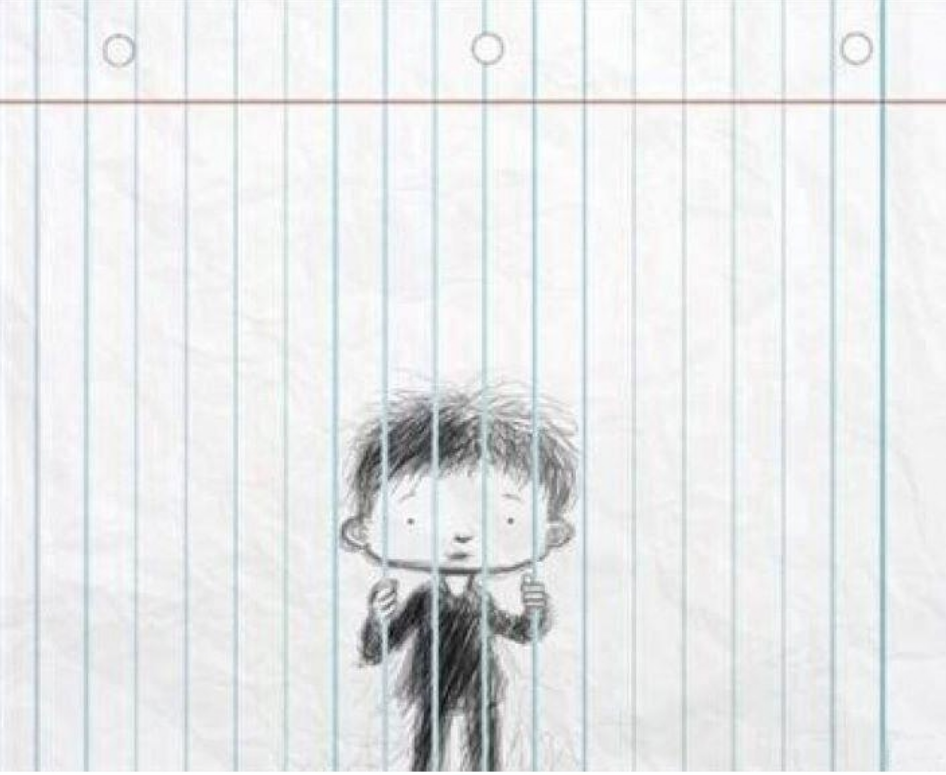

You’re buying lined paper at an abnormal speed

I swear I bought a new pukka pad last week and I’m already making notes on scrap paper. Where did it go?!

You worry about your argument in your daily life

Not arguments with real people, oh no. But the argument you’re meant to be having with all of the scholars you’re citing in your latest essay. Is my argument strong enough? Should I side with Winthrop or Koritansky? What is the meaning of all this?

You get the best ideas when you aren’t studying and write them all in your phone

No matter how long you spend in the library, you’ll get the best ideas for your work when you spend some time away from it. Then a ray of brilliance shines down on your thought process, and you’re on the toilet, or out with friends. Who are you texting? Myself, actually…

Your sense of humour revolves around ironic socio-cultural references

This probably explains the cheese and wine nights. Where else will we fit in?

You have dissertation complaint stand-offs with your course-mates

All discussions about final year projects have become a tirade of one-upmanship to vie for pity: I’ve only written 200 words. Yeah? I haven’t even decided on my title. Urgh.

Despite starting to smell like a library, you wouldn’t have spent your degree any other way than exploring the wonderful, fascinating, inspiring and challenging world of the humanities. Let’s face it, maths was never an option.